Typical Water Usage for a Family of 4

1. Introduction

During recent decades, the issue of water management has gained great involvement due to the constantly growing water demand, the express availability of global water resource, and the effects of climate change. Decision-makers strive towards utilization of optimal water exploitation regimes, realizing that new approaches need to exist adopted in lodge to optimize the apply of h2o resources. Scientific research, based on the latest technological advancements, seeks to plant reliable, constructive, and innovative solutions for integrated water management and water resource preservation. These efforts are reflected in the growing smart water management (SWM) paradigm, empowering a diversity of information and communication applied science (ICT) methodologies. Wireless sensor networks and communication technologies provide a powerful inventory tool to water operators, enabling them to oversee pregnant water parameters in real time [1,two]. In fact, basic monitoring of the water-related data tin can be extended with data analysis techniques to gain deeper understanding of the underlying processes and even further with predictive analytics. This contribution might evidence crucial to the challenges of future water management.

Managing h2o relies on heavy concrete infrastructure investments and inherently reactive governing attitudes; thus, controlling constitutes a challenging task for the operators, especially nether the framework of securing systems' sustainability and resilience. Compared to other disciplines, the water domain has not yet witnessed thorough investigation in terms of bringing together real-time monitoring, big data analysis, and auto learning with advanced control systems and the internet of things (IoT). Scientific enquiry focuses on optimizing private aspects of the h2o chain, while just recently information technology turned to the evolution of cyber-physical systems towards a holistic and digital-oriented arroyo to water management. Under this realization, the water management analytical platform (WMAP) brings a multifunctional advanced tool to the table which offers robust solutions in combining multiple types of data inputs and conducting analyses using multiple modeling frameworks, particularly when there is a goal of producing near-real-time predictions as the basis of controlling. Additionally, the ability to monitor and model water systems more accurately and respond more than chop-chop to unexpected changes could provide a basis for adaptive management. The hydro-environment community could benefit from the proposed tool by bringing powerful optimization capabilities to exercise and opening a wealth of opportunities for water direction practitioners.

In many cases, water distribution networks monitor groundwater and surface water bodies with a variety of sensors. Typical measurements include water level, pressure level and flow rate, water quality, etc. Related quantities such as precipitation, temperature, evapotranspiration, pumping water free energy, or data emerging from human behavior or remote sensing data are also relevant and are being nerveless by either water utilities or unlike environmental agencies [three]. Combining these data enables discovery of causative relations betwixt water need and need drivers by ways of demographic, socioeconomic, touristic, and infrastructure effectiveness indicators and provides an a priori knowledge on the patterns of water availability and demand [4]. Furthermore, all this knowledge can be used every bit an input to predictive algorithms and thus, water utilities and municipalities have the opportunity to plan h2o exploitation better, taking into business relationship a fast-changing environment (mainly due to climate change and population growth). Typical use cases, where users benefit from efficient data-driven analytics, are in prediction of surface or groundwater levels, prediction of water quality parameters, prediction of water demand on household, commune or urban levels, predictions of water need in agronomics, etc. In gild to exploit the water management data and implement intelligent solutions, a robust and efficient platform is needed. Some of the required functionalities include: data integration from heterogeneous (streaming) sources, data cleaning, enrichment and fusion, standardization of data access, and data mining and information-driven modeling capabilities that enable batch likewise equally existent-fourth dimension processing.

In this paper we describe an overall compages of the WMAP and its integration into a real-world scenario. The presented solution is based on the EU H2020 Water4Cities projection [5]. The architecture tin ingest big book of loftier-velocity data and process it either using online (close to existent-time) or batch settings. The outputs of the platform match the needs of the water management stakeholders as identified in Section 2.two. Our main focus is on the online processing. We present data collection, data cleaning, and missing data imputation techniques besides equally online contextual heterogeneous data fusion, which enables more accurate predictive analytics. Nosotros too introduce stream mining techniques for online processing into water management domain. The latter can finer address many big information-related issues in an IoT setting. In such a setting, the user is often faced with high-velocity data streams from a large amount of fairly independent sensors. The result of the independence is twofold: (1) information streams can exist easily processed in parallel (which means that this could exist accomplished even without the apply of modern tools for distributed processing similar Apache Hadoop, Spark [6] and others), and (2) stream mining models represent a computationally cheap solution to model the large amounts of data.

The contributions of this paper are every bit follows. (1) Nosotros present a conceptual architecture for WMAP, which we built upon our previous work on the numerous subcomponents. We developed our solution based on lambda [vii] and hut [8] architectures. We suggest refinements and particular implementation details of the architectures in guild to support the needs of the h2o domain. (ii) Our implementation supports real-world use case integration. The platform provides the complete pipeline for data analysis from its source (sensor, weather forecast, or other human-beliefs information) to the final product (i.east., data-driven prediction for groundwater level or household daily water consumption profile). (3) To the best of our knowledge, we have introduced stream mining methods into the water domain. Stream mining techniques meliorate the computational functioning of the pipeline and provide models that are meliorate at adjusting to the changes (concept drift) in the real-time data than traditional batch models. (iv) We integrated a solution for heterogeneous sources data fusion in a stream in the architecture, which enables contextual information to be included in the data-driven models and consequently increases the last accuracy of the models.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2.1 we present the relevant related work and explain the benefits of our arroyo. In Section 2.2 we present typical water domain utilize cases and respective data types. In Department ii.iii we nowadays the architecture, which is able to handle the previously identified data and its integration into a real-world organisation. Nosotros proceed by presenting detail components inside the architecture and corresponding results in Section 3 and finally we conclude in Section 4, where nosotros also provide insights into the futurity challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

two.one. Related Work

The literature proposes a couple of architectures that are suitable for large data processing within the internet of things (IoT) applications. The lambda architecture was proposed by Marz and Warren [7]. The architecture includes two independent pillars for large data processing, the batched processing (batch layer) and the stream processing (speed layer). The serving layer presents a view of the results. The hut compages [8] extends the lambda architecture by formalizing the data acquisition and message distribution (broker) components on the i hand and reduces the generic nature of the speed layer on the other. It reduces real-time processing to consequence processing, by which we lose the potential for real-time machine learning techniques. We advise two adjustments to the existing architectures: (1) We propose a concrete framework for realization of the speed layer in the lambda architecture which volition serve the needs of water direction domain. (2) We propose the extension of the hut architecture with existent-fourth dimension car learning components inside the speed layer (in dissimilarity to merely effect processing, based on the rules generated in the batch layer). Additionally, we suggest the existing hut architecture'due south principle to deploy models learnt in the batch layer to the speed layer, where predictions are generated on existent-time data. Stream mining is a well-researched topic [9]; however, it lacks real-world applications [10]. Many incremental learning algorithms exist. Amongst them are methods that are based on stochastic slope descent like recursive linear regression, support vector machines, and neural networks [11], methods based on determination and model trees and their ensembles [12] (i.eastward., streaming random forests) and incremental deep learning [13]. Many well-known platforms that enable big scale analytics (Apache Spark, Samza, and Flink), which are used in product systems, still lack implementations of more circuitous stream mining algorithms. Among platforms that practise enable incremental learning techniques we can notice university-oriented frameworks such as MOA [xiv], scikit multiflow [15], and other smaller projects dedicated to a unmarried algorithm only. The infrastructure is sufficient, but a unified production-oriented framework for stream motorcar learning techniques is needed. Nosotros have based our piece of work on QMiner [sixteen], which has been successfully deployed in many industry-grade employ cases (from energy management to world news monitoring to anomaly detection in large figurer clusters).

Our main contribution is related to the inclusion of advanced heterogeneous information fusion in the streaming setting. To the best of our knowledge, our methodology [17] is the just one that deals with information fusion in an online scenario. A like platform, IoT streaming data integration (ISDI) [18], also solves real-time data integration using the generic window-based algorithm epitome. The platform deals with the time alignment problems and inherent heterogeneity of the incoming streaming information; however, it solves the issue of data fusion with a batched algorithm on top of a relational database. Other methodologies are mainly focused on solving non-heterogeneous sensor fusion, which is non suitable for solving problems in ecology data-driven modeling [17]. The consequence has gained a lot of attention from the scientific community in contempo years.

In the water domain, the research focus on data analytics ICT systems is spread among various topics. Research has identified the potential of bogus intelligence techniques for deepening the understanding of the acquired IoT data and for aiding determination-making processes. Various architectures and functionalities have already been researched in several areas of water direction [19]. For instance, ref. [20] introduces a instance report where they deploy an IoT-enabled platform in order to gather information for precision agriculture and ecological monitoring. In some other case, ref. [21] presents a web-based platform for water efficient households. The platform enables consumers to monitor and control the water and energy consumption of their households in real time. From a hydrological perspective, a global web-based catchment area (river basin or urban subcatchment area for rainwater) hydrological information platform allows both scientists and non-expert users to hands access and visualize hydrological data for local-level water management and water stewardship in catchments [22]. Although the same ICT platforms provide advanced and innovative features for water direction, their design does not favor easy adaptation to other uses. Their principal drawback is the lack of support for standardized data commutation protocols, while they also need to address connectivity with additional data analytics tools. Our platform (WMAP) is implemented as an integrated support tool that has the potential to adapt to dissimilar stakeholders' needs, combining fast data acquisition, information fusion capabilities, and depression-computational stream mining methods.

On a conceptual level, the usefulness of a big information analytics platform for groundwater management has been recognized past the Southern African Development Customs [23].

two.2. Typical Utilise Cases and Data Description

There is a great range of typical scenarios where ICT systems accept the potential to improve efficiency and facilitate critical decision-making in the h2o domain. Precision irrigation, optimization of water distribution networks, preservation of environmental flows in lake and river ecosystems [24], prevention of extreme events (floods and droughts) forth with water-oriented urban planning, present merely a few interesting scenarios. Traditionally, h2o management has been driven by process-based models focusing on revealing the mechanisms of natural water resources and simulating the operation of water-related infrastructure. Although modeling provides reliable and useful insights in relation to critical parameters of the water cycle, its usability is express and ofttimes fails to produce timely solutions. The complexities and extensive detailing involved in the representation of water processes make the evolution of process-based models extremely challenging. Some of the major drawbacks arise from problems related to miscalibration, over parameterization, high computational requirements and extensive data preparation, while adapting to changes and capturing subconscious organization dynamics is oft incommunicable. Data-driven methods, on the other hand, bridge some of the shortcomings of the process-based models by relying heavily upon car learning methods. This gives them the ability to overcome the (in several cases) unknown physics of the modeled system by exploiting the information implicitly hidden in the data. In agriculture, data analytics can reveal the causal relations betwixt irrigation and crop production and assist with preparation of reasonable and precise irrigation schedules in compliance with environmental and socioeconomic aspects. Furthermore, predicting water availability and need, detecting anomalies throughout the water distribution organisation, and raising alarms in example of h2o quality deterioration present an important added value in urban water direction. In terms of lake and river ecosystems direction, predictive analytics can allow proactive interventions both in regulating environmental flows and preventing water quality degradation [25]. Floods and droughts, due to their devastating consequences on ecosystems, food supply and economies, present a rather sensitive sector, where the proposed platform could proactively predict such events and reveal the circumstances under which they may take place.

Since water management is often a circuitous procedure, encompassing diverse activities and involving different stakeholders, the optimal use of water resources implies a broad range of actions. Water system monitoring (by in situ sensors or remote sensing) is essential in order to understand the underlying behavior of disquisitional components of the arrangement. Monitoring includes data collection from various sources in (nigh) existent fourth dimension. In this paper, we presume that the underlying IoT infrastructure is already in place. Our tools provide a information management and analysis level on top of the sensor layer. Typical information sources in the water domain are (come across Table one):

Collected information tin be further analyzed and used for modeling. Data-driven forecasting has the potential to reveal organisation dynamics and produce meaningful and accurate predictions nigh the state of crucial organisation components. Thus, water experts and water operators volition take the advantage of obtaining the necessary knowledge to go on in constructive water management plans and secure sustainability of water resources.

Possible scenarios for usage of data-driven modeling are:

-

Providing water security in agriculture (predicting water availability and demand, regulating irrigation schedules, setting sustainable limits on water allotment);

-

Delivering water supply services (predicting supply and need fluctuations, predicting availability of water resources, securing adequate water quantity and quality, semantic annotation of water demand, detecting anomalies throughout the water distribution network in households or district areas in terms of leakage, theft, etc.) Securing h2o in aquatic ecosystems (specifying environmental flow regimes to achieve sustainability, identifying h2o contagion, and regulating the quality);

-

Reducing flood and drought take a chance (in-time storm h2o "hot spot" localization by operating early alarm systems, amalgam efficient flood control infrastructure, predicting drought events and taking the necessary preventive measures);

-

Promoting integrated urban water direction (IUWM) (suggesting possible locations of nature-based solution (NBS) interventions, designing land apply change allocation, assessing groundwater levels for urban planning extension).

Nosotros present 2 illustrative examples of typical water management use cases.

Case: Isle of Skiathos, Greece. Skiathos Island is a typical Greek isle with a loftier touristic influx during the summertime, which exceeds its population of 5000 inhabitants. The influx results in a sharp increase in water need during summer. This, combined with an anile distribution network with high h2o loss due to leakage, means the isle ofttimes faces water shortage bug during the touristic peak. The quantity and quality of groundwater, which serves as the isle's h2o supply, are beingness increasingly deteriorated; thus, the h2o operator was forced to accept actions towards a more efficient and rational water direction plan.

Balancing the h2o supply by means of water abstraction regulation, effective pressure control schemes, and improvements to ageing infrastructure will assist to rationalize the use of the finite h2o resources. Notwithstanding, the achievement of an effective direction authorities requires a thorough insight in relation to hydrological and hydraulic parameters and other related variables. Aquifer water level, water abstraction rate, force per unit area throughout the water supply network, seasonal water demand levels, touristic arrivals, weather predictions, etc., are some of the parameters that the h2o operator needs in order to utilize different water supply regimes in accordance with demand [26].

Additionally, in terms of water quality, measurements have shown mercury concentrations above the condom threshold in the groundwater. Thus, h2o cannot be used for drinking or cooking purposes and people plow to bottled water to cover these needs. Increased mercury concentrations are linked to high salinity in the water; therefore, it becomes important to quantify seawater intrusion, which entails measurements of groundwater level, temperature, and conductivity.

In social club to keep to a smart h2o monitoring scheme, the operator installed a range of wireless sensors measuring menstruation, pressure, water level, temperature, and h2o quality parameters, producing large amounts of real-time data. Notwithstanding, these data are not interoperable, so the h2o operator is faced with the need to install various different platforms to get access to the data, while whatever data fusion exercise is an arduous task. From this perspective, Skiathos presents a suitable instance for the implementation of our proposed water management analytical platform. The uniform admission to the data along with the implementation of information analytics and prediction algorithms will non only serve the efficient real-time data monitoring but will enable new insights into water management planning.

Case: Ljubljana urban region, Slovenia. The goal of the Ljubljana case report is to provide a reference organisation that will enable integrated urban water management (IUWM). IUWM is based on existing water supply and sanitation principles within an urban expanse by involving urban water management within the telescopic of the unabridged river basin [27]. The conceptual framework and approaches regarding a more efficient IUWM have evolved the past decades to involve new engineering science solutions, the idea of integration towards the holistic theory, and the public participation through awareness raising and participatory designing. The IUWM system should enable stakeholders to gain deep cognition of their water systems through the clever visualization of key design parameters, and a valid simulation that will consummate and interpolate their information. This way, hidden elements of the urban water cycle will be revealed also as cause–effect relations. Stakeholders, including citizens, will do good from optimum and inclusive design. There is a need to build an appropriate system that will enable IUWM decisions on an urban district level.

Nosotros establish the Ljubljana case study suitable every bit a reference system considering the urban surface area of the Ljubljana Urban center spreads between two rivers—the Ljubljanica and the Sava rivers, the latter existence the main Slovenian river discharging water from the Alpine mountains in the north-west of the country. The urban and agricultural area between the 2 rivers is where well-nigh 15% of Slovenian inhabitants live and piece of work and the main groundwater resource at the aforementioned time. Two recharging components of the Ljubljanskoaquifer, i.due east., the local atmospheric precipitation and infiltrated Sava River, are exposed to different sources of contamination considering they originate from different parts of the hydrological circle. The area of the city of Ljubljana has a long history of various flood protection measures. Nevertheless, many parts of the urban area of the city are still heavily threatened by floods, which are a consequence of intensive urbanization, surface run-off increase, as well as climatic change effects.

The utilise of data and communication technologies (ICT) enables IUWM by weighting the measure not only in comparison with comparable measures, but too against other aspects of planning [28]. It is important that any arrangement results are precise plenty to enable IUWM decisions (eastward.k., investments in infrastructure, city master plan rules); therefore, the big river catchment areas demand to be sliced into suitable sub–catchment areas on an urban district level. Freshwater, wastewater, and storm water found the parts of the urban h2o cycle, while the urban surface, the aquifer, and water supply infrastructure constitute the linking mediums that intervene in the natural water cycle, forcing an contradistinct, disturbed urban water bicycle. The level of disturbance determines the consequences for water availability, water quality, and the regime of flows that with the increase of extreme events may (or already) found a severe threat to social integrity, urban infrastructure, the economy, and the natural environment. The architecture should support ingestion of the identified data sources and provide mechanisms to perform the usage scenarios. The interaction of groundwater with other urban systems, such every bit infrastructure and surface water networks, is well recognized by proficient practitioners and is increasingly important to the everyday city agenda [29]. Therefore, the first step towards the IUWM reference system in Ljubljana is presented with groundwater level sensor data.

2.3. Architecture

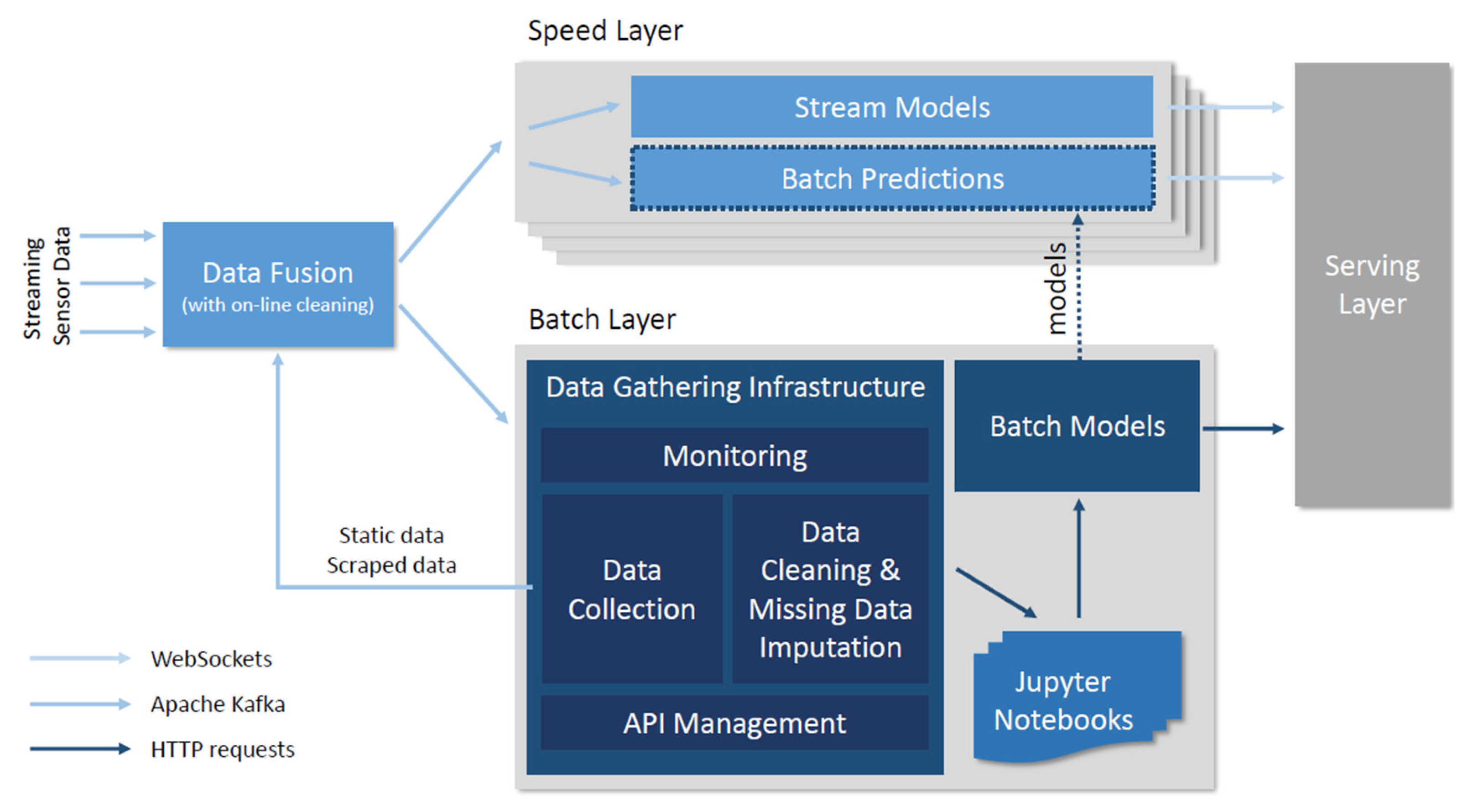

Lambda [seven] and hut [8] architectures provide a solid basis for building the h2o management belittling platform (WMAP). According to the identified usage scenarios in the water direction domain, we advise a couple of modifications which are depicted in the WMAP architecture in Figure 1.

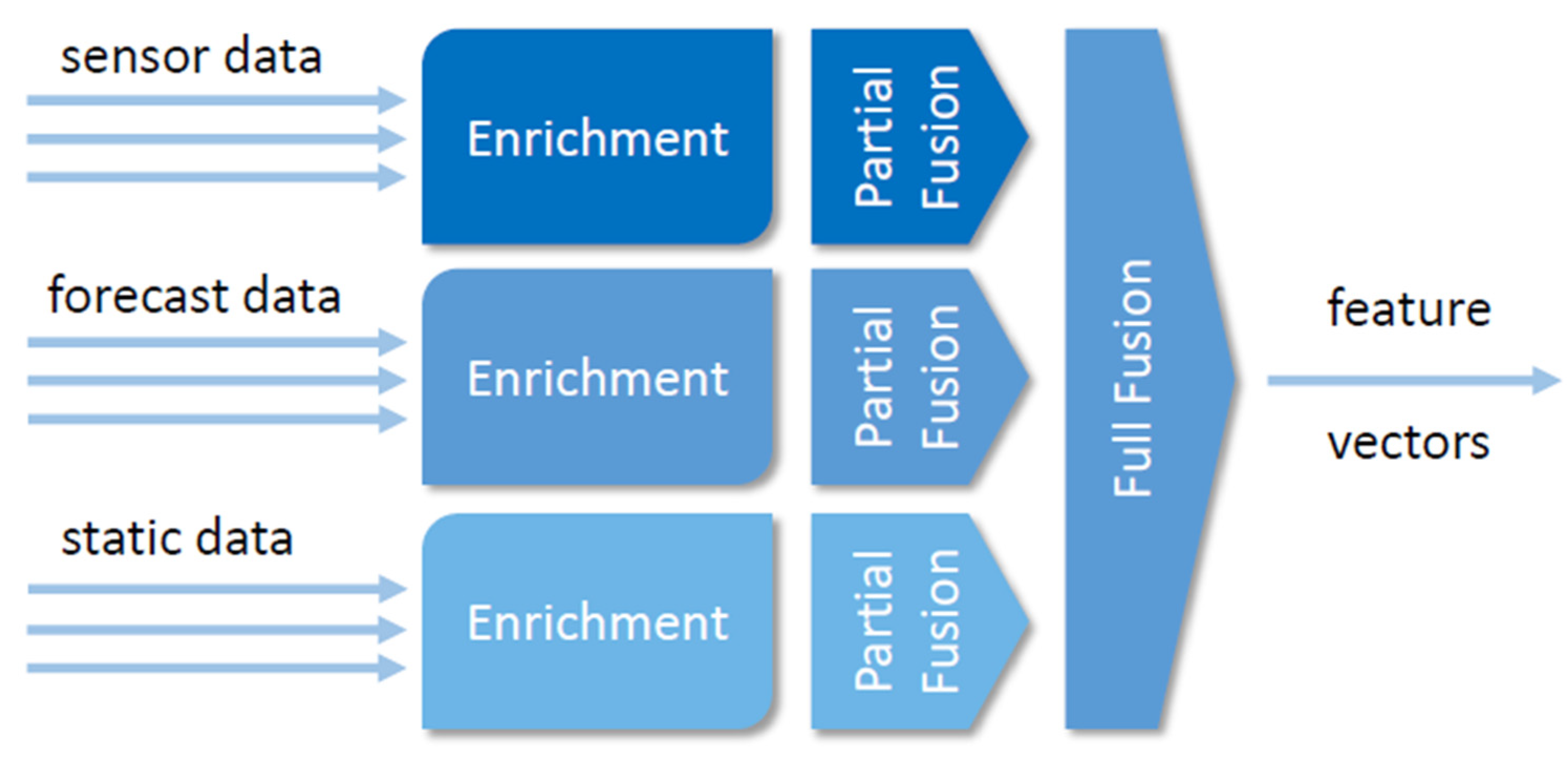

Arrows in the figure depict data flows. Streaming data is handled by Apache Kafka infrastructure in the back end and with Spider web Sockets (which can be ingested by HTTP clients) in the serving layer. Static data, spider web resources, and communication within the batch layer are handled with HTTP requests. The data enters the framework straight from sensors (and respective adapters) and from information drove in the data gathering infrastructure (from dissimilar web resource that need to be polled for the data). All the data undergoes the initial online data cleaning and fusion. The data fusion component is depicted in more detail in Figure 2. This component provides ingestion of different heterogeneous data streams (including unlike streams from the internet of things, weather condition forecasts, and static data on homo behavior). All these streams are enriched (with different aggregated values of the stream). In the next pace, we join the streams together with special attending to their records' original timestamp. Finally, we compose the feature vectors. Fused (characteristic vectors) are injected into speed and batch layers and used for predictions of further modeling. Raw information is also pushed into the batch layer for further offline analysis. It is worth noting that nosotros propose the usage of data-driven machine learning models even in the speed layer (nosotros do not limit information technology to result processing). Technologies like heterogeneous streams data fusion and stream mining provide fast alternatives to traditional information-driven analytics. Finally, results are exposed via the serving layer.

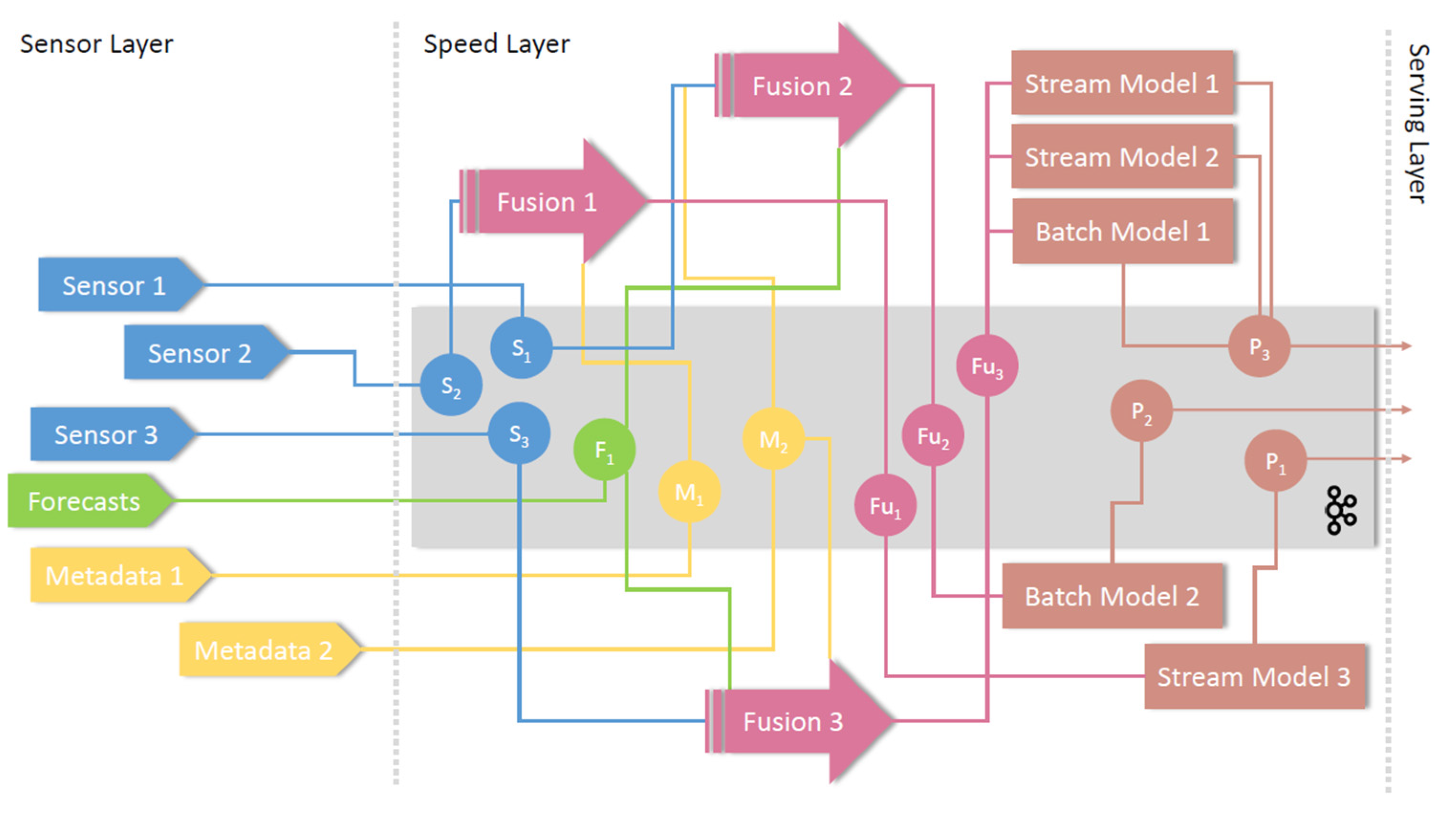

The speed layer consists of two different predictive models: stream models (which are based on incremental learning) and batch predictions, which implement batch models developed in the batch layer. Both components provide similar functionality; nonetheless, incremental models are updated with each new measurement whereas batch models need to be updated from the batch layer. As shown in the data clarification, the uses in water management consist of larger number of contained information-mining bug. Parallelization of the computational tasks in such a setting emerges naturally. Each apply (sensor) is contained and requires express needs for computation power. Therefore, the load can simply be balanced over a set of workers, which are connected past data distribution infrastructure equally depicted in Effigy 3. The whole streaming pipeline (information fusion and speed layer) is generic and is described in more detail in related work [17].

The batch layer includes data gathering infrastructure (a information layer that tin eat, store, and serve large volumes of data according to the specific use, and is able to perform information cleaning and missing data imputation) and batch models with Jupyter Notebooks to back up machine learning on top of these data. The aim of the batch models component is twofold: (one) the learned models is fed into the batch predictions component in the speed layer, and (2) data-mining process results are provided from the batch modeling component, which is useful for on-demand processing. The layer also includes monitoring and API management (to handle availability and access to the information).

2.4. Notes on the Implementation of Speed Layer

An illustrative example of the implementation of the speed layer is depicted in Figure i. Sensor, speed, and serving layers are positioned from left to right. The gray rectangle depicts the data distribution infrastructure, which takes care of transferring streaming data betwixt components. The blue color depicts components and data flow related to sensors (IoT). The light-green color represents forecasts (i.e., weather forecasts). The yellow color represents static metadata sources. Data fusion components are depicted in majestic, and finally the modeling components and its predictions are depicted in brown.

Data are flowing from left to right, originating from sensors or other sources, being infused into advisable message channels or topics (depicted as circles) in the information distribution infrastructure and then consumed by different instances of fusion components. These components can consume data from the same or from a different set of sensors, forecasts, and static metadata sources. Here the data are enriched, validated, consolidated, and finally merged into viable characteristic vectors suitable to be consumed by machine learning models. The models (either batch or stream based) eat the information from fusion bulletin channels and provide results to prediction message channels. Multiple models tin consume data from the same fusion message channel, meaning that we tin hands provide multiple predictions with heterogeneous properties for the aforementioned scenario.

At that place are many viable platforms to be used for bulletin distribution. We accept integrated Apache Kafka (https://kafka.apache.org/, accessed on 1 January 2022), which seems to be the favorite choice in terms of performance and functionality, and RabbitMQ (https://world wide web.rabbitmq.com/, accessed on 1 January 2022) in some cases. The data fusion component has been implemented with QMiner (http://qminer.ijs.si, accessed on 1 Jan 2022), which enables big-scale data analysis and provides methods (stream aggregates) for enrichment and consolidation of the heterogeneous streaming data. Stream models accept been implemented using the same framework, but experiments have been performed also with Scikit-multiflow (https://github.com/scikit-multiflow/scikit-multiflow, accessed on 1 January 2022) and MOA (https://moa.cms.waikato.ac.nz/, accessed on 1 Jan 2022), which offering a larger diverseness of algorithms. However, none of the platforms for stream learning algorithms has reached the maturity that could enable it to be used in production setups with ease and confidence. Batch modeling has been developed using Python scikit-learn (https://scikit-acquire.org/, accessed on 1 January 2022) library.

Particular parts of the platform are described in the Department iii. Every subcomponent of our architecture has been described in a separate paper, which is cited in every subsection below.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Information Gathering Infrastructure

Data gathering infrastructure was implemented as function of the batch layer and is depicted in the lesser of Figure two. The layer is described in more item in related work [30]. It consisted of a data collection component, which controlled subscribing, polling, and preprocessing of external information sources. The latter tin can include remote devices, sensors, external information access APIs, and other web resources. A congenital-in feed monitoring component provided the ability to notify different stakeholders about failures and anomalies in the incoming data streams. The data were stored in a MongoDB NoSQL database. The latter allowed treatment of data records with flexible schema. We take identified this as a useful characteristic, since some feed formats may evolve over time and records from unlike time intervals may contain dissimilar information fields. Additionally, the batch layer offered cease users secure and compatible access to the data and like shooting fish in a barrel integration with widely used data analysis tools such as Jupyter Python and R notebooks, Matlab scripts, and others. The information gathering infrastructure could also exist used to trigger stream simulations, which are helpful for testing and development of streaming models. Loosely coupled data drove components could exist scaled horizontally in guild to improve performance.

In Water4Cities scenarios, we have stored the information near groundwater levels, pump sensors, and weather information. Special attending was given to the ease of integration of different data sources by providing boilerplate lawmaking in diverse languages (Python, Coffee, JavaScript). The platform operation has been proven adequate in the traffic domain, where nosotros retrieved and stored approximately 100,000 records per hour (records include images and heterogeneous sensor data for Slovenia), collecting more than than 1.2 TB of information per year. With just this amount of data, we could monitor the whole center of Ljubljana with water smart meters with an update interval of 15 min in every household. As data collection components could be distributed to different machines, the bottleneck was represented by data storage [31]. Even with a single high-finish server the authors were able to reach throughput of 1882 records per second, which is equivalent to 1.6 1000000 records in 15 min. Such a setup would exist adequate for the whole Ljubljana region and the database could have been scaled horizontally by adding new machines to balance the organization load.

iii.ii. Missing Data Imputation and Data Cleaning

Co-ordinate to the Well-baked-DM methodology [32], the process of information mining is devised into six divide stages. Modeling itself represents only 1 of these stages and the majority of a data scientist'south work fourth dimension is invested in a process of understanding and preparing data. Data preparation includes data transformation, data cleaning, missing data imputation, and also data fusion, which is described in Section 3.3. Algorithms for data cleaning and missing data imputation differ significantly between the speed and batch layers. Within the speed layer, the algorithms should exist uncomplicated and efficient and should rely only on historic data of a time series in question. They should too be autonomous and should not rely on whatsoever expert intervention, as the data stream is continuous. We proposed the usage of the Kalman filter's short-term prediction capabilities in order to address outlier detection (cleaning) and sporadic missing sensor readings in a data stream [33]. In the batch layer information technology is viable to use more complex and therefore more than effective models that can rely on any information within the dataset and exploit the power of motorcar learning to detect optimal models for missing data imputation as well every bit for bibelot detection, as described by [34].

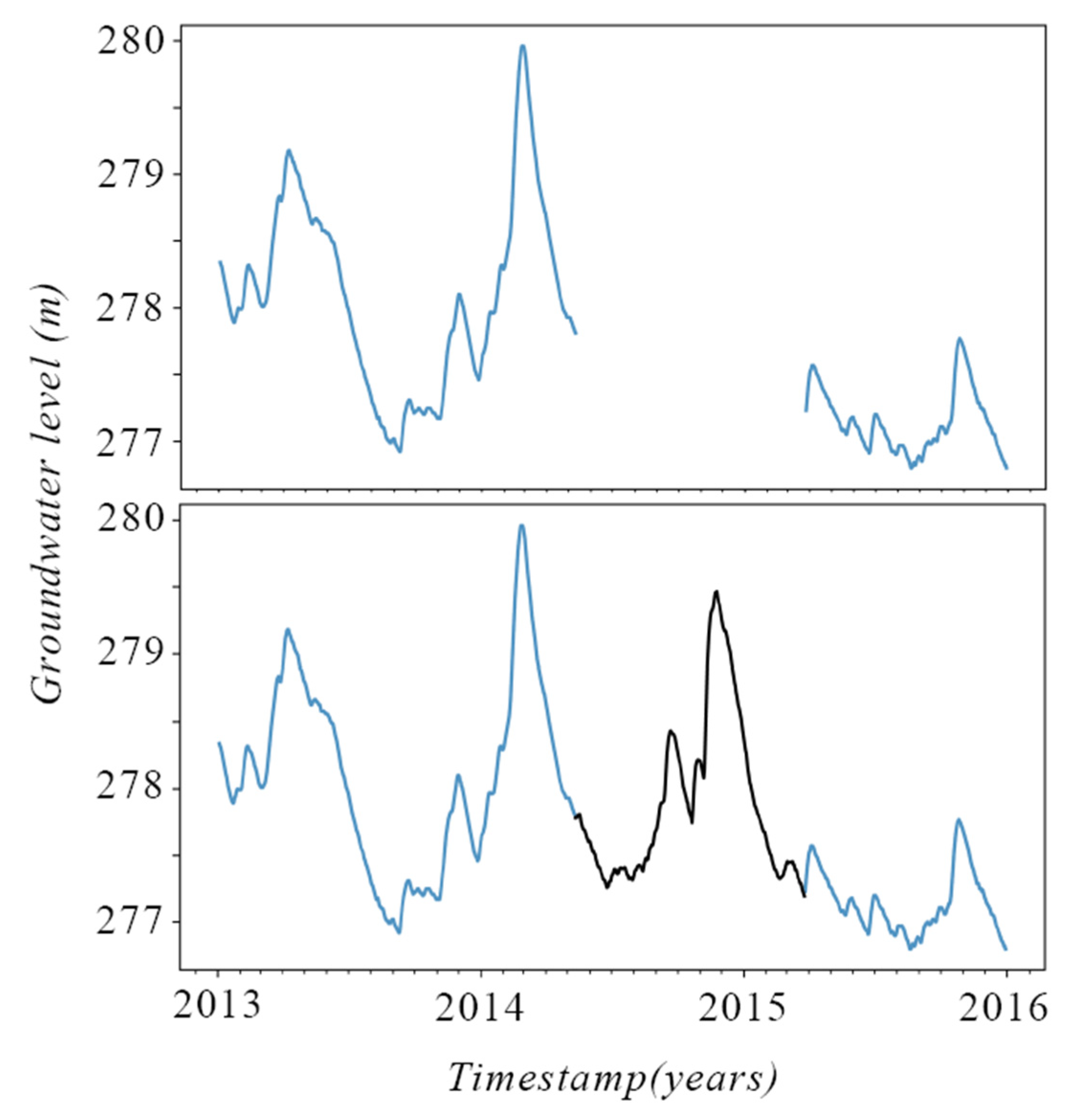

An instance of the results of the missing data imputation algorithm on a "Ljubljana polje" groundwater levels dataset [35] is depicted in Figure 4. Nearby sensors were used to predict the missing values of another sensor. High accuracy of the methodology suggests that the data from the sensors were reliable. Accurateness of the sensors maintained by Slovenian Environment Bureau is ±0.01 yard [36].

For groundwater level data in the Ljubljana region, we were able to achieve loftier Rtwo > 0.997 scores for highly correlated sensors (correlations up to 0.98) and were able to improve scores significantly for sensors with low correlation to nearby sensors. A more detailed clarification of the dataset, methodology, and results is given in related piece of work [34].

3.three. Existent-Fourth dimension Heterogenous Data Fusion

An intrinsic holding of big information is its heterogeneity [37]. In a WMAP system, heterogeneity has been observed regarding data delay (data are submitted via various legacy systems, which bring systematic constant lags, sometimes send data in batches every 60 minutes or every day, etc.), data frequency, data blazon (i.e., weather forecast time serial is updated every hour whereas the sensor stream is coherent in regard to its time component). To provide efficient and accurate predictive models, the usage of multiple data sources is essential. Feature vectors that contain additional enriched and contextual data will usually provide additional information to the predictive models and finally result in better prediction accuracies. To the best of our cognition, our solution [17] is the first to mathematically describe and solve this problem.

The data fusion compages within the speed layer is depicted in Figure 2. There are 3 bones tasks to be accomplished within the data fusion: stream enrichment, partial fusion (of sources of the aforementioned type), and full fusion. The stream processing component supports ingestion of three different types of streams: sensor information (which might have various frequencies and delays), forecast data (which is beingness updated regularly, i.e., conditions forecasts are updated every hour for the next 48 h), and other contextual and human being-behavior data (commonly static pre-generated information, which we include as a stream in our platform).

Every information stream was separately transformed (i.e., nosotros transformed weather predictions into a number of regular information streams) and enriched with stream aggregates (i.eastward., moving averages, variances, minimums, and maximums in different time windows).

Final feature vectors were generated from fractional feature vectors within the fusion component, where time consolidation was done. Fourth dimension consolidation is a process in which nosotros bring all the partial feature vectors to the same master time (we handled delays and different update frequencies here; we also provided constant sampling; i.e., every 15 min a feature vector was generated, which is essential for most machine learning techniques). Finally, the fusion component expands the characteristic vector with historic data or even some derivatives (i.e., departure between hourly moving averages in the past hour), which oft provide viable information to the information models. Final feature vectors are provided to stream or batch models, which summate terminal predictions.

To the best of our knowledge, no methodologies described in the scientific literature tin can match the expressiveness of our system's characteristic extraction linguistic communication and cannot handle heterogeneous streaming data fusion. Every bit argued in the next subsection, such data fusion is beneficial for improved prediction accuracy. In that location are, however, no direct validation methodologies for data fusion systems, especially not for the online versions' latencies.

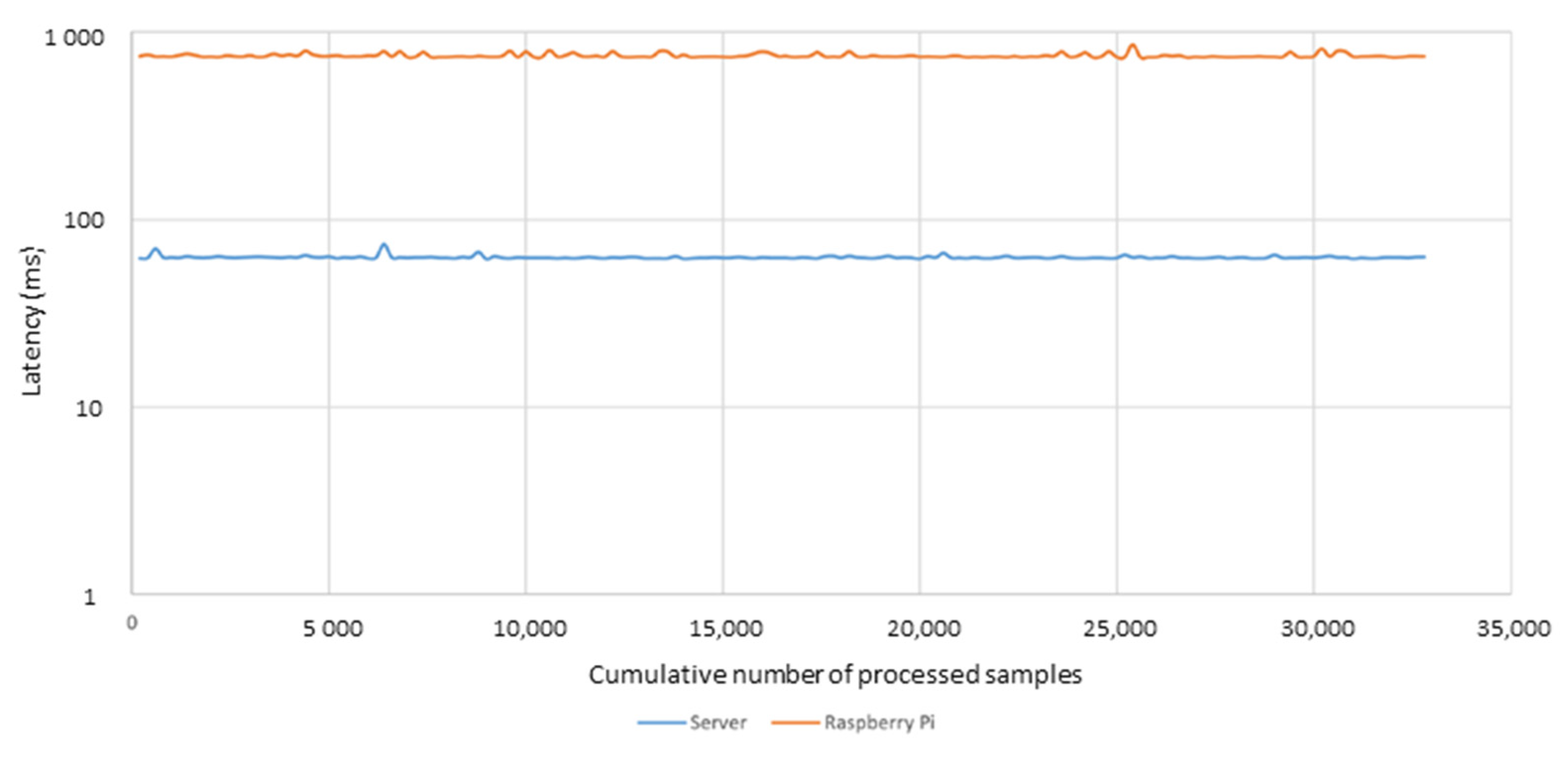

When profiling the pipeline, information technology is evident that the data fusion system works much faster than the optimal prediction algorithm. On a server machine, the average time to procedure the message in the online information fusion framework is 0.2 milliseconds (Figure 5). However, a prediction step with the random forest method takes on average 63 milliseconds on a server and 740 milliseconds on Raspberry Pi two (Figure 5). It is, therefore, important to have an architecture to be able to parallelize the processes (in our instance any number of data fusion, stream models, and batch predictions could exist running distributed in the network, reachable by message distribution organisation). The lesson learned in the functioning validation of the system was that the message distribution system (i.e., Apache Kafka) has to be optimized within the network. If not, the bottleneck tin be in the bulletin distribution and not necessarily in the processing power.

three.iv. Data-Driven Modeling

Based upon the feel in the other fields that have faced the artificial intelligence breakthrough in recent years (physics, remote sensing and world ascertainment, energy direction, etc.), nosotros propose to bring the information (for batch analysis) to the users and permit them manipulate the data in the way that is standardized or is based on the tools they are already familiar with. Our information gathering infrastructure provides a compatible access point for heterogeneous data sources and provides basic boilerplate code to speed upwardly data analysis and development. An expert tin access the data in the tool of their preference (i.e., Jupyter notebook), perform assay, and fifty-fifty deploy their own models to the production by just updating respective configuration structures (feature vectors and models).

As demonstrated in more detail in related piece of work [38], a fourth dimension series based on groundwater level sensor information can exist enriched with various derivatives and with appropriate contextual data. Models volition benefit from features such as readings of level modify in the past hour, past twenty-four hour period, or past week, moving average in the by twenty-four hours or past five days, or even by calendar month. Weather and especially celebrated weather data (precipitation, snowfall and modify of snow coating) from the area and respective river basin, aggregated over a longer menstruum (typically 1 week) will bear witness good correlations with groundwater level modify and will improve the models significantly. In particular areas, the fourth dimension of the twelvemonth might expose some typical local dynamics, etc. As stated in the related piece of work department, other generic stream processing platforms do not enable heterogeneous sources information fusion and tin can therefore not easily provide enriched feature vectors which yield more than accurate predictions. In add-on, our data fusion component enables like shooting fish in a barrel manipulation (with a single configuration structure) of stream aggregates (such every bit moving averages or variances) and their celebrated values.

Experiments take been conducted on the Ljubljana polje aquifer dataset [35], which is likewise available via an endpoint (information gathering infrastructure API) exposed by the platform, described in this newspaper (check the dataset source for boosted instructions on how to use the API). The dataset includes more than 600 groundwater stations for Slovenia, which measured groundwater levels between years 1950 and 2018. A subset relevant for the Ljubljana polje aquifer was used in the experiments. Weather data were provided by Slovenian environs agency (ARSO) and were also included in the dataset. Normalization has not been performed on the information, since tree-based methods do not benefit from information technology and because the features themselves are in the same order of magnitude, which should be sufficient for the convergence of the linear regression models.

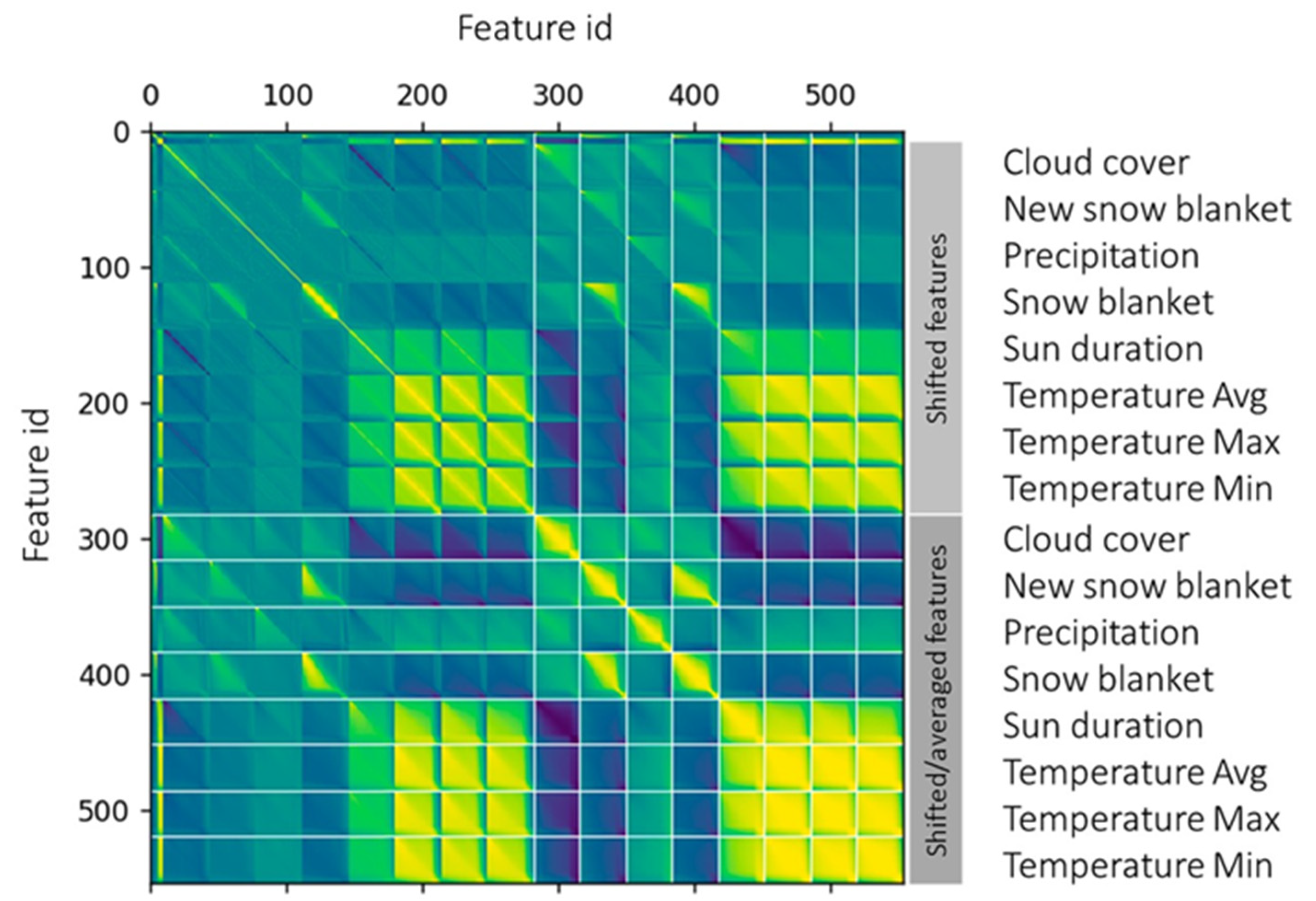

Characteristic correlation matrix for one of the fourth dimension-serial is depicted in Effigy half-dozen. It includes groundwater level features and weather features. Initial features are from the original dataset. The others have been extracted from historic values. Conditions features accept been averaged by various intervals (from 1 to 100 days) and different averaging windows have been considered. Side by side, these features accept besides been shifted by different time intervals in order to compensate for the time needed for weather-related phenomena to have effect on the groundwater. Based on the correlation matrix we have chosen features from the acme 100 features correlated with the target value. Best- and mutually least-correlated features (co-ordinate to Figure 6) have been selected for each feature subset (aggregated data, aggregated atmospheric condition data, shifted historic weather condition data). All the raw values accept been considered in the models. Correlations of features with the target value vary from −0.iv to 0.78 (precipitation averaged over next 3-day weather forecast is the all-time correlated feature). The feature choice process tin be achieved using a more than thorough search through the grid of features. Greedy algorithms would not be able to reach this task in a reasonable fourth dimension; even so, smart heuristics powered by genetic programming and entropy-based similarity measures can canvas the most relevant sections of the feature infinite and excerpt (nearly) optimal feature vectors from a large characteristic space, ordinarily further improving accuracy of a item model [39].

Accuracy of the models has been evaluated using R2 score. R2 is invariant to starting time the target value from 0 (which is not true for other relative scores like mean average percentage error—MAPE) and to amplitude inside the dataset (which influences the root mean squared error—RMSE). Rii is therefore suitable for comparison of different approaches.

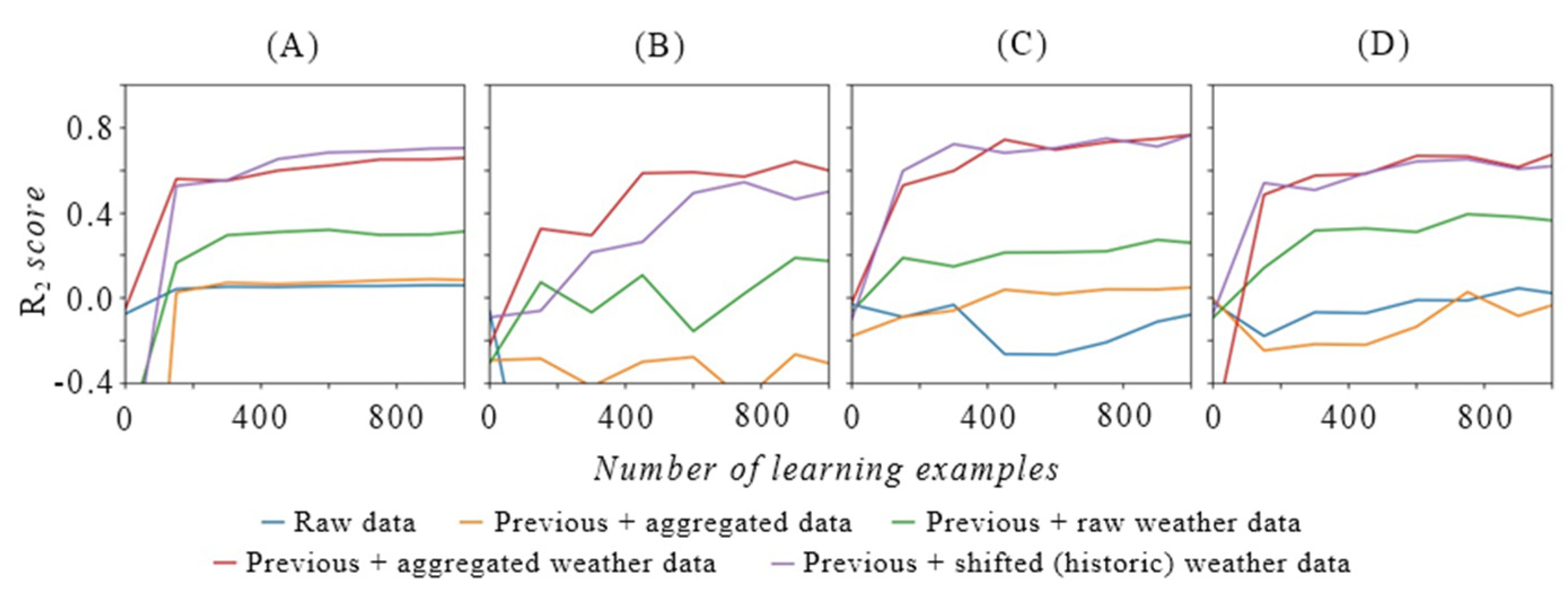

Figure 7 depicts learning curves (improvement of R2 score with number of training examples) of different models for prediction of groundwater levels (with 3-day prediction horizon) in the Ljubljana region. Each model (defined by a learning algorithm and a feature set) is represented past a curve in Figure 7A–D. Curves with a larger number of contextual features are college in the learning curve graphs, which indicates the benefits of the methodologies presented in this paper. Figure 7A depicts results based on linear regression, Effigy 7B on determination trees, Figure 7C on slope boosting regression and Figure 7D on random forests.

In every picture we tin notice five unlike curves that represent five unlike feature sets. The blueish curve represents a feature set with just direct features from the groundwater level time series, the orange curve represents the "blue" feature set enriched with various stream aggregates, the dark-green curve represents a feature set which besides includes electric current weather data. The cherry-red curve is based on the results from a feature set which is further enriched with various aggregations of weather data, and finally the violet curve models include besides time-shifted weather features to reflect the potential hysteresis issue of weather on groundwater levels.

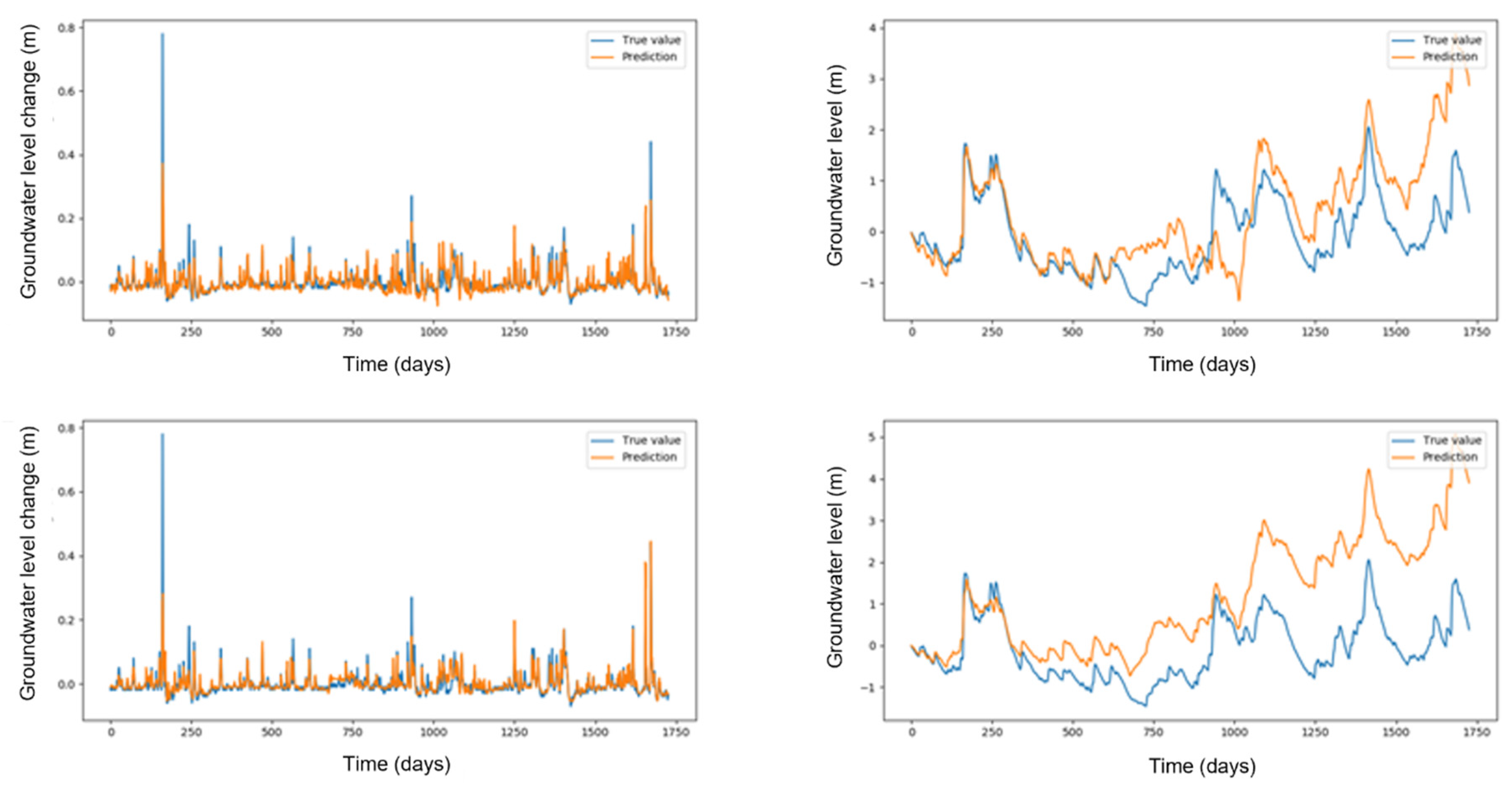

Case results for groundwater level predictions (using linear regression and gradient boosting) are shown in Figure 8. Nosotros take modeled daily changes of the groundwater (depicted on the left side of Effigy 8) and then calculated cumulatives (on the correct side of the same figure). Cumulative values show how well the model captures the dynamics of groundwater levels. The values themselves diverge from the truthful values, merely the important information is that the models reflect the trends in the existent world well.

Each consecutive dataset includes more potentially relevant features that enable the model to reflect the underlying procedure meliorate. Results, represented with blueish and orangish lines, which only include features based on the groundwater level fourth dimension series itself, behave even worse than a constant zero model. Every bit soon equally additional atmospheric condition data are considered (green line), the accurateness improves drastically. The biggest improvement is withal achieved by including different time-window and time-shifted aggregates of weather information, which seem to reverberate dynamics of groundwater adequately. The linear regression in Figure 7A gives stable results (curves rise with the number of learning examples). Each addition to the characteristic set increases the accurateness of the model by bringing new knowledge. Conclusion trees in Effigy 7B behave slightly worse and are much less stable. Nosotros also discover that decision trees learn slower. They need more than examples to reach comparable accurateness to linear regression. The learning charge per unit of slope boosting regression in Figure 7C and random forests in Figure 7D matches the speed of linear regression. Random forests, which are unremarkably the method of choice in environmental data-driven modeling, comport best with the raw weather dataset (light-green) and aggregated weather dataset (cherry), just slightly worse than linear regression in the best-example scenario. The best results are given by gradient boosting regression, which tin can accomplish an Rii score close to 0.8. As a baseline, a model with only the best characteristic would yield R2 ≈ 0.six, which is 0.16 less than the results of gradient boosting with the all-time feature subset.

Usage of data-fusion and data-driven modeling inside the speed layer of the compages enables real-fourth dimension application of the predictive analytics, adult in batch mode.

iv. Conclusions

We have presented a water domain view on the data mining approaches inside a smart h2o management scenario. We take identified the needs of stakeholders and provided a description of typical data sources that support achieving the desired results. We accept presented an architecture based on standard large data approaches and an early on epitome which enables offline analysis tailored to the stakeholders' needs and real-fourth dimension predictive analytics that tin can be practical to real-world scenarios. The platform provides parallelization of data processing, which enables horizontal scalability of the arrangement. The measurements, even so, demonstrate that even a single high-stop server can support a reasonably big project with up to 400,000 connected IoT devices. The main contributions inside the streaming part of the architecture (speed layer) are the data fusion component and the usage of computationally less demanding stream mining techniques for predictive analytics.

Although a lot of work has been done in the field of digitalization in the water management domain, there is still a gap to be bridged in the water management domain to attain its counterparts in energy management, traffic, and manufacturing. Many solutions have been developed in those fields, especially in energy management, which can be applied to the water domain. Understanding of dynamics in the h2o domain has traditionally been supported past process-based models, which require extensive knowledge of the domain, including geology and fluid dynamics. With more data provided, motorcar learning models can provide an efficient alternative to the existing state, just considering they are easier to implement, because they reflect the current state of the organization immediately (including human behavior-related variables), because predictive techniques take been proven to mimic hidden process dynamics and because they can exist toll constructive. As both approaches, data-driven and process-based, have their ain advantages, they should work hand in mitt, which offers another research challenge for the futurity. On the other hand, the water community has to embrace and gain trust in data-driven approaches. We should therefore allow the community to perform their analysis with the tools they are already familiar with or with the tools that are well documented and widely used in the data mining community (i.east., scikit-learn with Jupyter notebooks). In club to maximize the accuracy of data-driven models, information fusion techniques (like we have described in this paper) will be of the utmost importance. Weather plays an important function in the modeling of water-related phenomena. An efficient generic way to input weather data into the models is needed. The weather condition information are like (in structure likewise as in volume) to the remote sensing data from Sentinel and LandSat systems. The water direction community (as well agronomics or others from the ecology domain) should take advantage of efficient technologies for exploiting earth observation data that has been evolving fast in recent years.

Finally, all this noesis will accept to be integrated under a standardized framework which will enable an efficient substitution and processing of large amounts of high-velocity information streams enriched with appropriate contextual data. An effective provisioning system for deployment of models is needed in order for the framework to take total advantage of parallel processing and to successfully deploy the system within a large sensor network. We have depicted the foundation for such a organization, but efficient management of the analytics components still remains a challenge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K.; methodology, K.K.; software, K.K., M.S., and N.One thousand.; validation, Northward.Thousand. and P.P.; data curation, Thou.Grand.; writing—original typhoon preparation, Thou.One thousand. and Northward.Chiliad.; writing—review and editing, P.P., K.S.; visualization, Thousand.S., K.G.; project assistants, K.K., Northward.Chiliad. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has received funding from: (i) the Eu Horizon 2020 Programme project Water4Cities under grant agreement number 734409, (2) the European union Horizon 2020 Programme project NAIADES under grant agreement number 820985, and (iii) the PRIMA Foundation projection MAGO with grant number 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Argument

Not applicable.

Information Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank partners and colleagues from H2020 Water4Cities project for their contributions in the stage of grooming and writing of this paper. We would like to give thanks Stamatia Rizou and Anja Polajnar, for projection leadership and steering of the work, Kristina Klemen, for insights into the needs of the urban planning community for the solutions provided past data-mining approach, Filip Koprivec and Matej Ćerin, for developing subcomponents of the WMAP system, and finally Dimitris Kofinas and Chrysi Laspidou for providing significant insights into the water management domain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no part in the blueprint of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The post-obit abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| Crisp-DM | Cross–industry Standard Process for Data Mining |

| HTTP | Hyper–Text Transfer Protocol |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| IoT | Net of Things |

| ISDI | IoT Streaming Data Integration |

| IUWM | Integrated Urban H2o Management |

| MOA | Massive Online Assay |

| SQL | Structured (English) Query Language |

| SWM | Smart Water Direction |

| WMAP | Water Management Belittling Platform |

References

- Laspidou, C. ICT and stakeholder participation for improved urban water management in the cities of the hereafter. Water Util. J. 2014, 8, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cominola, A.; Giuliani, M.; Piga, D.; Castelletti, A.; Rizzoli, A. Benefits and challenges of using smart meters for advancing residential water demand modeling and management: A review. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 72, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.E.; Laspidou, C.S. The Water-Energy Nexus at Urban center Level: The Example Written report of Skiathos. Proceedings 2018, 2, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, S.H.; Magiera, East.; Froelich, Westward.; Jach, T.; Laspidou, C. Domestic water consumption monitoring and behavior intervention by employing the net of things technologies. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 111, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizou, S.; Kenda, K.; Kofinas, D.; Mellios, N.; Pergar, P.; Ritsos, P.D.; Vardakas, J.; Kalaboukas, K.; Laspidou, C.; Senožetnik, M.; et al. Water4Cities: An ICT Platform Enabling Holistic Surface Water and Groundwater Management for Sustainable Cities. Proceedings 2018, two, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, M.; Xin, R.S.; Wendell, P.; Das, T.; Armbrust, M.; Dave, A.; Meng, X.; Rosen, J.; Venkataraman, Due south.; Franklin, Chiliad.J.; et al. Apache spark: A unified engine for big data processing. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marz, N.; Warren, J. Big Data: Principles and Best Practices of Scalable Realtime Data Systems, 1st ed.; Manning Publications Co.: Greenwich, CT, Usa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ta-Shma, P.; Akbar, A.; Gerson-Golan, G.; Hadash, G.; Carrez, F.; Moessner, K. An Ingestion and Analytics Architecture for IoT Applied to Smart City Employ Cases. IEEE Net Things J. 2018, 5, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C. Data Streams: Models and Algorithms (Advances in Database Systems); Springer: Secaucus, NJ, Usa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krempl, G.; Žliobaite, I.; Brzeziński, D.; Hüllermeier, E.; Concluding, M.; Lemaire, V.; Noack, T.; Shaker, A.; Sievi, S.; Spiliopoulou, M.; et al. Open up challenges for data stream mining research. ACM SIGKDD Explor. Newsl. 2014, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.B.; Chen, 50.; Siew, C.1000. Universal approximation using incremental constructive feedforward networks with random subconscious nodes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2006, 17, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonomovska, E.; Gama, J.; Džeroski, S. Online tree-based ensembles and selection trees for regression on evolving information streams. Neurocomputing 2015, 150, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, 50.T.; Chen, Z.; Li, P. A survey on deep learning for big data. Inf. Fusion 2018, 42, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifet, A.; Holmes, 1000.; Kirkby, R.; Pfahringer, B. MOA: Massive Online Analysis. J. Mach. Acquire. Res. 2010, 11, 1601–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel, J.; Read, J.; Bifet, A.; Abdessalem, T. Scikit-Multiflow: A Multi-output Streaming Framework. CoRR 2018, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- QMiner: Data Analytics Platform for Processing Streams of Structured and Unstructured Data. Available online: https://www.researchgate.internet/publication/269100309_QMiner_Data_Analytics_Platform_for_Processing_Streams_of_Structured_and_Unstructured_Data (accessed on i January 2022).

- Kenda, Grand.; Kažič, B.; Novak, E.; Mladenić, D. Streaming Information Fusion for the Cyberspace of Things. Sensors 2019, xix, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, D.Q.; Kayes, A.; Rahayu, Due west.; Nguyen, Yard. ISDI: A New Window-Based Framework for Integrating IoT Streaming Data from Multiple Sources; Springer: Heidelberg, Federal republic of germany, 2019; Volume 926, pp. 498–511. [Google Scholar]

- Manes, C.50.; Laspidou, C. Biosensors for Aquaculture and Food Rubber. In Challenges and Innovations in Ocean In Situ Sensors: Measuring Inner Ocean Processes and Health in the Digital Age, 1st ed.; Delory, E., Pearlman, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Kingdom of the netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Popović, T.; Latinović, Northward.; Pešić, A.; Zečević, Ž.; Krstajić, B.; Djukanović, S. Architecting an IoT-enabled platform for precision agronomics and ecological monitoring: A case written report. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 140, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossieris, P.; Kozanis, South.; Hashmi, A.; Katsiri, Eastward.; Vamvakeridou-Lyroudia, L.; Farmani, R.; Makropoulos, C.; Savic, D. A Web-based Platform for Water Efficient Households. Procedia Eng. 2014, 89, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchment Hydrology Explorer for Water Stewards (CatchX Platform). Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2018EGUGA..20.9882A/abstract (accessed on one January 2022).

- Gaffoor, Z.; Pietersen, K.; Jovanovic, N.; Bagula, A.; Kanyerere, T. Large data analytics and its function to support groundwater management in the Southern African evolution community. Water 2020, 12, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laspidou, C.; Kofinas, D.; Mellios, N.; Latinopoulos, D.; Papadimitriou, T. Investigation of factors affecting the trophic state of a shallow Mediterranean reconstructed lake. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 103, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellios, N.; Moe, S.J.; Laspidou, C. Car Learning Approaches for Predicting Health Risk of Cyanobacterial Blooms in Northern European Lakes. H2o 2020, 12, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofinas, D.; Mellios, N.; Papageorgiou, E.; Laspidou, C. Urban h2o need forecasting for the island of Skiathos. Procedia Eng. 2014, 89, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, J.N.; Tucci, C.; Goldenfum, J.A. (Eds.) Integrated Urban H2o Management: Humid Torrid zone: UNESCO-IHP; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, United states of america, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oregi, Ten.; Roth, E.; Alsema, E.; van Ginkel, M.; Struik, D. Apply of ICT tools for integration of free energy in urban planning projects. Energy Procedia 2015, 83, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricker, Due south.; Banks, V.; Galik, One thousand.; Tapete, D.; Jones, R. Accounting for groundwater in hereafter metropolis visions. State Employ Policy 2017, 69, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senožetnik, M.; Herga, Z.; Šubic, T.; Bradeško, L.; Kenda, Chiliad.; Klemen, Grand.; Pergar, P.; Mladenić, D. IoT Middleware for H2o Management. Proceedings 2018, 2, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.A.; de Morais, Due west.O.; de Freitas, Due east.P. NoSQL real–time database performance comparison. Int. J. Parallel Emergent Distrib. Syst. 2018, 33, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, C. The CRISP–DM model: The new pattern for data mining. J. Data Warehous. 2000, 5, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kenda, G.; Mladenić, D. Autonomous Sensor Information Cleaning in Stream Mining Setting. Bus. Syst. Res. J. 2018, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenda, K.; Koprivec, F.; Mladenić, D. Optimal Missing Value Estimation Algorithm for Groundwater Levels. Proceedings 2018, 2, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groundwater Levels for Slovenia–Data Set. Bachelor online: https://researchgate.net/publication/336239471_Slovenia_-_groundwater_levels (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Andjelov, M.; Frantar, P.; Mikulič, Z.; Pavlič, U.; Savić, V.; Souvent, P.; Uhan, J. Groundwater quantitative condition assessment for River Basin Management Program 2015-2021 in Slovenia. Geologija 2016, 59, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Ten.; Zhu, X.; Wu, G.; Ding, Westward. Data mining with big data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2014, 26, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kenda, K.; Ćerin, Chiliad.; Bogataj, Grand.; Senožetnik, One thousand.; Klemen, K.; Pergar, P.; Laspidou, C.; Mladenić, D. Groundwater Modeling with Motorcar Learning Techniques: Ljubljana polje Aquifer. Proceedings 2018, 2, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprivec, F.; Kenda, G.; Šircelj, B. FASTENER Characteristic Option for Inference from Earth Observation Data. Entropy 2020, 22, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1. Proposed modification of lambda and hut architectures for usage in the water management domain. Heterogeneous input information streams are fused in the information fusion component and pushed into both speed and batch layers. The speed layer includes two types of models—incremental (being updated with only new information online) and batch. Batch models are updated with all the information from the batch layer.

Figure 1. Proposed modification of lambda and hut architectures for usage in the h2o management domain. Heterogeneous input data streams are fused in the information fusion component and pushed into both speed and batch layers. The speed layer includes two types of models—incremental (being updated with only new data online) and batch. Batch models are updated with all the data from the batch layer.

Figure 2. Blueprint of information fusion component in the speed layer. The component is able to ingest iii types of information streams and output a stream of feature vectors.

Effigy two. Design of data fusion component in the speed layer. The component is able to ingest three types of data streams and output a stream of feature vectors.

Figure 3. Example of speed layer implementation and interconnection of particular components. Bulletin distribution component is depicted in grayness.

Figure 3. Case of speed layer implementation and interconnection of particular components. Message distribution component is depicted in gray.

Effigy iv. Example of missing information imputation algorithm based on nearby sensors, R2 > 0.99. The dataset with missing information is depicted in the top panel. The imputed function of the time series is depicted in black in the lower panel.

Figure 4. Example of missing data imputation algorithm based on nearby sensors, R2 > 0.99. The dataset with missing information is depicted in the pinnacle console. The imputed part of the time series is depicted in black in the lower panel.

Figure 5. Evaluation of the performance of the speed layer setup (information ingestion, streaming data fusion, and modeling with random forest) on a loftier-terminate server (bluish) and Raspberry Pi edge device (orange). Apache Kafka was running in a dockerized container on the same high-end server.

Figure 5. Evaluation of the performance of the speed layer setup (data ingestion, streaming data fusion, and modeling with random forest) on a high-end server (blue) and Raspberry Pi edge device (orangish). Apache Kafka was running in a dockerized container on the same high-end server.

Figure half dozen. Correlation matrix includes 544 features. The features are the original ones represented in the dataset (such equally weather information and current and historic groundwater levels) and derived ones (such as averaged and shifted past different time intervals). Our platform enables online generation of all these features. Positive correlation is depicted in yellowish and negative in dark blue shades.

Figure half-dozen. Correlation matrix includes 544 features. The features are the original ones represented in the dataset (such every bit weather information and electric current and historic groundwater levels) and derived ones (such as averaged and shifted by different time intervals). Our platform enables online generation of all these features. Positive correlation is depicted in yellow and negative in night blue shades.

Figure 7. Learning curves of apparently and enriched datasets with multiple learning methods: (A) linear regression, (B) conclusion trees, (C) gradient boosting regression, (D) random wood regression.

Figure seven. Learning curves of plain and enriched datasets with multiple learning methods: (A) linear regression, (B) decision copse, (C) slope boosting regression, (D) random forest regression.

Effigy 8. Groundwater level change predictions and summed predictions over time. First row depicts linear regression results, the 2nd row depicts slope boosting results. Summed predictions may drift over fourth dimension, which does non give an objective measure out of the model's accuracy. Capturing the right trends is much more important.

Figure 8. Groundwater level alter predictions and summed predictions over time. First row depicts linear regression results, the second row depicts slope boosting results. Summed predictions may drift over time, which does non requite an objective measure out of the model's accuracy. Capturing the right trends is much more than of import.

Table 1. Typical data sources in the h2o domain and corresponding indicative subcategories.

Table 1. Typical data sources in the water domain and corresponding indicative subcategories.

| Typical Data Sources in the Water Domain | Indicative Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Surface and groundwater bodies information | groundwater level and pressure; permeability and storage capacity; river h2o level and belch rates; flood inundation areas |

| Meteorological data | precipitation; temperature; evaporation; wind speed; radiation |

| Water repository data | attainable storage book; water storage bathymetry and level; reservoir or tank water level; storage inflows, outflows and offtakes |

| Water exploitation data | book of water taken from groundwater, rivers, lakes, and storage infrastructure; water pumping data |

| Water quality information | temperature; pH; oxygen; nutrients; chlorine concentration; conductivity |

| Water pollutant data | heavy metals concentration; fertilizers; pesticides; bacteria; algae |

| Water distribution data | flow rate; pressure level; energy consumption |

| Human being-behavior data | water consumption; migration/tourism; public participation data |

| Spatial data | infrastructure; time to come and electric current state use; water bodies; static data based on previous measurements and process models; surface and topology; geological data; risk maps |

| Administrative data | water direction expanse boundaries; water prices; water infrastructure inventories |

| Publisher'south Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/5/2886/htm

0 Response to "Typical Water Usage for a Family of 4"

Post a Comment